While making my latest artist video (Lee Bontecou) I came across this quote by her in Smithsonian Magazine, September 2004, A meticulous artist and craftsperson, Bontecou was at an installation of her work. To make a repair she said to one of the crew, “See if you can find that paste used by plumbers. Plumbers,” she repeated, “not electricians.” Installation supervisor Brad Martin said, “Here’s an artist who actually makes her own work. That’s really old school! A lot of contemporary artists don’t know how to do that.”

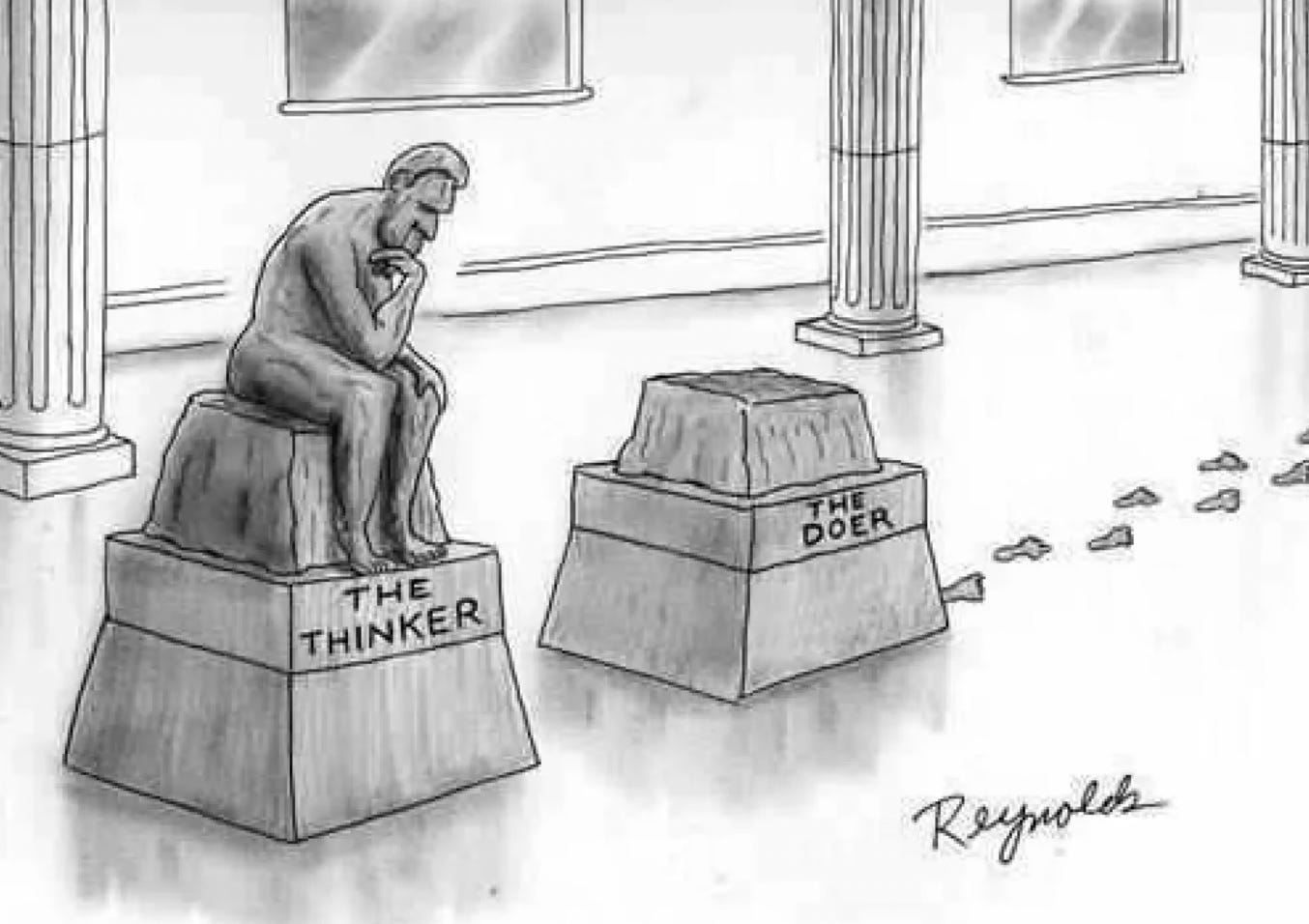

This surprise at an artist who actually makes her own art struck me. The topic is not new—conceiving vs. doing—but it continues to astonish me that it’s wholly acceptable for a non-creating artist (“artist”?) to employ a talented person/group of persons to execute on an idea and yet these people receive no acknowledgment (or royalties.) Rationalize it how you will—work-for-hire, artisan/craftsperson vs. Artist (cap A!) but it still reeks of exploitation. Didn’t the Writer’s Guild just strike for 148 days over a similar issue—the right to receive fair remuneration for creative work?

For me the art-going experience is three-fold: the context (both physical and historical), the subject matter and the execution—take one of these “legs” away and the chair falls down. How can execution not matter?

There are two types of artists who don’t make/entirely make their own work. Those who have the skill but, due to time constraints, hire helping hands and the skill-less who hire others to execute for them.

Italian renaissance art boasts a long collaborative tradition dating back to the 13th century. Initially, workshops were comprised of families working together and passing on traditions. Not unlike a mentorship today, groups such as the Della Robbia family were headed by talented artists who instructed succeeding generations. Point being that competency at the top reigned supreme. Due to public demand and the inescapable limits of time the family workshop model expanded to include unrelated aspiring artists. Rubens, DaVinci, Michelangelo etc. engaged artists who would one day, thanks to their employ, make a name for themselves as well as receive greater compensation.

Contemporary artist Robert Longo is a current example of the workshop-model tradition. In July 2021, I saw his exhibit Storm of Hope at the Palm Springs Art Museum which consisted of impressive, photo realistic, “large-scale drawings in charcoal to create what he calls ‘the perfect image.’” I later learned these drawings were sketched out by Longo but completed by uncredited, über-talented assistants. The fact Longo had the skill set to create his works mitigated somewhat for me the fact that others had been employed to complete it. I understand they were paid but to quote Bontecou, Longo’s not “selling things.” He’s creating unique works presented in a museum setting for viewers to contemplate as such. This exposure increases his market value and therefore his bank account. Why not give credit and a percentage, however small, of the proceeds to the masterful few who help complete his vision?

The same can be said but with more moral conviction (mine) about those highly-successful, dare I say, producers who couldn’t make a work of art if someone pointed a paint gun to their head. Why are we calling it art?

I once worked in a home décor company. Product designers created an item, a bowl say, which was then outsourced to an overseas manufacturer where workers, still exploited but in a more clear-cut fashion, reproduced the product—some quite beautiful—which was then shipped back to the US where salespeople sold it into stores for the consuming public. These products were never defined or sold as “art” and, given the mass production, lost their exclusive quality that in part defines fine art.

Following this logic, why is Jeff Koons designated an artist? Why not call him what he, and others like him, is: a product designer/brilliant marketeer? The magic of a Jeff Koons balloon dog lies in the fact that a hive of freakishly-talented people managed to make mirror-polished stainless steel look like rubber. A knowledge set that has nothing to do with Koons and never will. He’s certainly not the first to introduce trompe l’oeil and won’t the last. Why can’t the fabricators who bring his delirious visions to life be acknowledged and, given the wealth these products generate, fairly compensated. The same argument could be made for Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst, Takashi Murakami and Ai Wei Wei (100 million, handmade porcelain sunflower seeds, anyone?) to name a few.

An artist is defined as “a person who practices any of the various creative arts, such as a sculptor, novelist, poet or filmmaker.” So, long live the imagineer, those whose abilities lie in envisioning the new but fall short of giving shape to their vision and let’s, at the very least, publicly acknowledge the shape givers without whom their imaginings would lie dormant.

Comments? Questions? Please share and thanks.